Marketers’ “familiarity” with their own category may lead them to overestimate the fame and underestimate the uniqueness of their brand assets, say Ehrenberg-Bass academics.

Marketers’ judgements on the strength of distinctive brand assets are “rarely accurate”, according to research from academics associated with the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute.

The academic paper, published in the Journal of Brand Management, compares marketers’ intuitive judgement about distinctive brand assets to consumers’ knowledge. The results suggest intuition around brand assets is not a reliable substitute for consumer research, with marketers prone to overestimating the fame of assets and underestimating their uniqueness.

In other words the research finds marketers assume that brand elements are, on average, more effective at evoking memories of the brand among consumers (fame), and they judge assets to be less effective at being linked with just one brand (uniqueness). However, the research does find marketers are more likely to accurately make judgements on the fame and uniqueness of stronger brand assets.

The paper is authored by Ruby Brus, Nicole Hartnett, Margaret Faulkner and Carl Driesener, all current or former academics at the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute. The Institute has been at the forefront of research around distinctive brand assets, which are sometimes referred to brand elements or fluent devices.

In the paper, published last month, brand elements are defined as assets like logos, colour and taglines, which make up a brand’s identity and help “consumers to recognise the brand”. Strong brand assets can help marketers signal their brand to consumers in different settings.

Of course, it is the resonance of brand assets with consumers that really matters to judge their strength. When it comes to a decision around dialling up, building or retiring a brand asset, it is the consumer’s view of that asset which matters. However, some marketers, particularly those who feel they have a good understanding of their customer, may feel they can rely on their intuition to judge the strength or their own (and indeed even competitors’) assets.

The research finds a significant gap between marketers’ intuition around how brand elements will perform with consumers and consumers’ actual associations.

A perception gap

The consumer research tested more than 400 brand elements from brands across different categories. The strength of these elements were determined across the two vectors of fame and uniqueness.

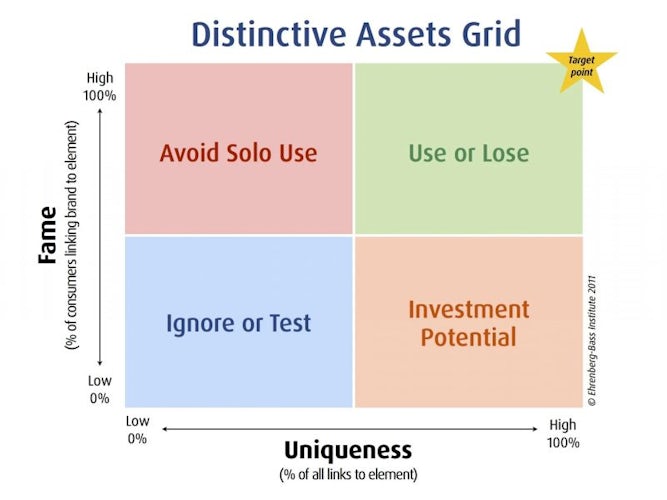

The study leans on the distinctive brand asset grid developed by Ehrenberg-Bass Professor Jenni Romaniuk. This grid plots fame on the Y axis and uniqueness on the X axis. The strongest assets are those that appear in the top right-hand corner, meaning they rank highly on both fame and uniqueness.

The grid format is used in the paper to compare marketers’ estimation of brand asset strength versus consumers, and demonstrates a lack of accuracy in marketers’ perceptions.

Their inability to accurately judge consumers’ reaction to brand assets occurs across both vectors of fame and uniqueness. However, while marketers are likely to overestimate the former, they are more prone to underestimate the latter.

Overfamiliarity with category brand assets is to blame for this, the authors hypothesise.

“It appears that marketers are projecting their own familiarity with brand elements in their category onto consumers, when they have much more exposure to these brand elements than the general population of category buyers,” the paper says.

This overfamiliarity could not only lead to marketers assuming brand assets are better-known than they actually are among consumers, but also lead to them overestimating the likelihood of consumers getting mixed up between them, the researchers suggest.

The right to play with distinctive assets first requires ruthless consistency

“High familiarity with competitor brand elements may also make marketers overly sensitive to perceived design similarities for brand elements between brands,” they say.

The implications for marketers are that judgement and intuition alone are rarely sufficient to judge the strength of brand assets among consumers.

“Making decisions on this basis alone risks poor performance and/or wasted resources,” says the report.

The obvious solution is to ensure consumer research is used as part of any decision-making process around brand assets. However, if there are budgetary or other limitations preventing this, the paper advises making decisions in a group setting, with the research finding this sort of group judgement was more likely to be accurate.

In summary, the research finds marketers who rely on their own judgement to determine the strength of distinctive brand assets risk making poor decisions.